I use flashcards a lot. To learn English vocabulary, the grammar, new programming languages, technical jargon, useful commands, and so much more. If I want to retrieve something from memory without going through a Google search, flashcards are my secret weapon since many years. Until now, I created thousands of flashcards manually and even more programmatically. While flashcards are simple to create (just a note with a question on the front and the answer on the back), creating effective flashcards may not be obvious at first. By following the rules present in this article, you will avoid most of the errors I made.

|

Some examples concern programming. If you are not a programmer, don’t panic, you don’t need to answer the flashcards to understand the logic behind them and the motivations to rewrite them. |

More is better than less

Creating flashcards take time, a lot of time. As a consequence, I am often reluctant to add too many flashcards because it’s just not funny to create them. At the beginning, I was copying whole blocks of text based on books, sometimes even screenshots. It was an easy way to push a lot of content to review. These flashcards are no longer existing in my decks. I have deleted and/or refactored all of them, without any exception.

Example

List<?> list = new ArrayList<Dog>();List<? extends Animal> list = new ArrayList<Dog>();List<?> list = new ArrayList<? extends Animal>();

|

Note for non-programmers

Programs are written in languages that have precise grammar rules, like in English. This flashcard illustrates different syntaxes, some valid and others invalid. A program can only run if the syntax is perfectly valid, unlike English, where someone will understand me even if I make mistakes, probably like in this blog post. |

This flashcard is based on a quiz present in a certification book and has many flaws:

-

As it tests different syntax rules, there is not a single answer. You can be right for the first option and wrong for the two last options. A good flashcard should have a unique valid answer. You can’t be partially right or partially wrong.

-

Consequently, you will need to revise the whole flashcards even if you already know the answer for most of the options, losing precious seconds that can be devoted to more tricky flashcards.

Example (refactored)

List<?> list = new ArrayList<Dog>();

List<?> foo = new ArrayList<? extends Animal>();

List<?> list = new ArrayList<? extends Animal>();

Advantage: By splitting into multiple flashcards, you learn each underlying rule at a different pace (on this example, the 3rd rule is the harder and take more time to assimilate). In this way, you don’t have to review already assimilated cards, and for each flashcard, either you know the answer or you don’t. It’s obvious to say if the flashcard was easy or hard.

Short is better than long

As a consequence of breaking the first rule, when you avoid creating many small flashcards, you end up with verbose flashcards (particularly for the back card).

Example

|

Note for non-programmers

Git is a program that keep the history of changes you do in a set of files. Programmers use it to keep the history of changes for the source code of a program. After each update, each developer pushes his modifications. Git makes sure there aren’t two developers who have changed the same code, and records a new commit, a kind of number to identify the changes. Developers can restore a previous state at any time by specifying an old commit. |

The problem with verbose back card is there is too much information to be able to say with confidence how easy it was to recall. Some of the information is harder to remember, and some of the information does not even deserve to be remembered. The solution is to follow the previous rule More is better than less, and split the flashcard into many smaller ones (and also delete the original flashcard, even if it took you a lot of time to create it initially).

Example (refactored)

git log master..experiment?

git log experiment --not master?

git log master...experiment?

git log master...experiment?

git log master..experiment and git log master...experiment?

|

Note for non-programmers

Git is mainly used by entering commands on a terminal, even if there exists graphical tools that let you click on buttons to get the same result. |

Advantage: Short flashcards are faster to read, you can revise more cards in the same time, review sessions are more fun because flashcards are really testing you (you know the answer or you don’t), and often the flashcards are more challenging because you can focus on tricky points, which also increase the satisfaction to learn them.

|

Tip

A good flashcard (front or back) must fit on your smartphone screen without scrolling (using a 5 inches screen size). |

For the front card, I avoid long, elaborate, question and favor direct question.

Example

git, which option could be used to get the list of possible commands?

git commands?

For the back card, I systematically remove all useless words, to make the answer as concise as possible, without losing meaning.

|

Note for non-programmers

Software applications send informational messages to record what they do in order to help the developer to debug when problems happen. They are called syslog messages and can be sent to another machine, using various guarantees. For high-traffic applications, you can use UDP to send the messages but they will not be resent if the message is lost in transit. Otherwise, you can use TCP to make sure the message is retransmitted. |

Advantage: The faster to read, the faster to review, but don’t go to far. You should never have to deduce the question or think hard to understand what the answer means. Write in basic English. No need to be William Shakespeare when writing flashcards.

Two-way is better than one-way

Creating a single flashcard is rarely enough. Learning is more complex. For example, the three-period lesson, a hallmark of Montessori education, was devised by the French physician Edouard Seguin, and helps young children learn vocabulary and concepts, following 3 steps:

-

Naming (Introduction) "This is a dog.",

-

Recognizing (Identification) "Show me the dog."

-

Remembering (Cognition) "What is this?"

All 3 steps are important, otherwise you can learn to recognize the dog, but fail to name it when you see it. You have to learn two related but different things. Flashcards are particularly well adapted to this system. For example, Anki can create for you a reversed card to be sure you learn the information in both ways. This model is very useful when learning foreign vocabulary. For example, you may want to recognize the word voiture in French texts and be able to translate the English word car when speaking French.

When it comes to determine the right number of flashcards to create, context is everything. Sometimes, one flashcard is enough, and sometimes, more than two flashcards are necessary. For example, if you want to read some French books, you can create only flashcards with French words on the front and English translations at the back, but if you want to speak French during your next trip to Paris, you better have to create flashcards with English words (or pictures) on the front, and French translations at the back.

In practice, starting with the right number of flashcards is far from easy. I’m still failing. When this happens, I recognize my failure and I update my deck to add new flashcards and/or deleting existing ones. Learning is an iterative process.

Example (continued)

git log master..experiment?

This flashcard help me understand the command if I come across it on Internet or on a coworker’s terminal, but does nothing to help me remember it the day I really need to run it. I learn the information only one way. The solution is to create the reversed flashcard.

experiment branch that hasn’t yet been merged into your master branch.

|

Note for non-programmers

This new flashcard is nothing more the definition of the previous command reformulated as a question. You can safely ignore the details. |

Example

The tendency to see the world as a place full of easily explainable events with simple causes and simple effects (financial crisis is caused by bankers, loss of jobs is caused by immigrants,...) instead of assuming things are more complex than that.

I often create similar flashcards when I come across a new concept, or a new jargon. This way, when I see the expression cited again, I already know the meaning and are not diverted by it, and so, I can read more advanced book on the subject. The problem is that if you give me the definition, the name will only be on the tip of my tongue. I need the reversed card to fully learn it.

Advantage: Flashcards should reflect the ways you will use the information. Create as many flashcards as necessary to prevent the tip of the tongue phenomenon.

Specific is better than general

As said before, a flashcard should have a unique valid answer. You should never ask yourself if you answered correctly or not.

Example: (Agile)

This method helps grasp a problem definition.

The flashcard is short but you don’t really understand what is expected. There are many valid answers with such a general question. The solution is again to use the More is better than less rule to replace the flashcard with more specific ones:

A good way to make flashcards more specific is to use cloze deletions. Cloze deletion is the process of hiding one or more words in a sentence. These flashcards are sometimes called fill-in-the-blank flashcards.

Example

Using cloze deletion, we can rephrase the flashcard like this:

Example

In practice, there are often several valid ways to create a flashcard. Let’s reuse the example from the rule Two-way is better than one-way:

The flashcard can be rewritten to use cloze deletion:

Or

Personally, I was using cloze deletion parsimoniously at the beginning, but now, I use them massively as I found them quickly to answer.

Advantage: fill-in-the-blank flashcards make the question crystal clear and make sure the answer is specific. When the answer is displayed, there is no possible doubt.

|

Tip

Anki provides native support for cloze deletion. Check the manual. |

Opened is better than closed

Answering yes or no to a flashcards is not optimal, and very often, you’d better rewrite the flashcard to ask for a more elaborate answer.

Example

|

Note for non-programmers

A file is splittable if you can read only a part of it without having to read the full content. Not all file formats are splittable. For example, you need to uncompress a zip file entirely even to read a single file present in the archive. |

The problem with flashcards like those is you are not learning really practical information. Being able to answer yes or no is not going to take you very far. Compare with this flashcard:

If you can answer this flashcard, you know for sure if the bzip2 format is splittable or not, and you can also explain why.

Advantage: Flashcards asking for closed questions are not funny. Open questions helps you learn a little more, and overall, can make a great difference. But don’t be too general… (see the rule Specific is better than general).

Subtle is better than obvious

A flashcard should never be too obvious, otherwise, you will answer correctly but fails to really learn the fact behind it. The solution is to formulate the question in a way that does not influence the answer (in practice, being subtle is far from being obvious).

Example

The question gives a clue that it may not be a plural form. Compare with this alternative:

The answer is still the same, but with this reformulation, you are influenced to find a solution while there isn’t. You will answer correctly only if you are sure that the word shrimp can be used in singular and plural forms. In this way, you test your knowledge, and not your capacity to suppose the answer.

To follow the rule More is Better Than Less, you’d better create complementary flashcards with noun that have a plural form ("What is the plural form of the word fox?"), even if that is the nominal case. Otherwise, if you only create flashcards for exceptions, you will learn to recognize these flashcards and be able to answer correctly without paying notice to the question ("Oh yes, I remember some words don’t have a plural form, the answer is No"). By introducing variations, you are required to consider the word (shrimp, fox) to answer ("Oh yes, I remember some words don’t have a plural form, what about shrimp?").

Example

She never wears hat.

This flashcard seems not so easy at first. There is no clue to find the answer. But with time, you will learn to recognize the sentence and be able to find where the error is. The day you need to write a similar sentence, however, you will probably hesitate between the two options. Indeed, you learned to recognize the error but failed to learn the rule. Compare with this alternative:

The solution is still the same but this flashcard force you to consider the rule. You can’t just learn to recognize where the error is located. You need to know the rule to answer the question. This flashcard seems less subtle than the first version because we mark explicitly where the problem is, but by providing the two possible options, you make the rule explicit.

Advantage: Make sure to learn the rule and not just to detect the error. When you know the rule, you are able to spot errors. The reverse is not true.

Mixed is better than (to much) organized

Flashcards should be organized. You cannot just put every flashcard on a big box and revise them together. You probably don’t want to chain "How to say hello in French?", "What is the Linux command to check available disk space?", "What is the capital of Japan?". Even if our brain is organized as a giant network of interconnected neurons, sometimes, a little organization is welcome. Anki lets you group your flashcards in several decks to revise them independently (French, Geography, Capitals). But too much separation is not necessarily a good thing to me:

-

It’s hard a review a large number of decks each day. You will not have new cards every day for each deck, and as soon as a deck fails to get new cards to learn, it loses some interest (learning is funnier than revising).

-

Our brain has a wonderful aptitude to bring together unrelated information to create new ideas. Reviewing each subject separately go against it and by doing so, you lose one of the main benefits of flashcards. There are, however, subjects that are best kept separated. If you aspire to become a polyglot, I’m not sure mixing vocabulary for French, Italian, Spanish, Chinese, Danish will be profitable (but I may be wrong). This can create confusion and slows down your progression. On the contrary, interspersing Unix, Git, Emacs, VS Code commands will help you see the similarities (e.g., Bash uses Emacs shortcuts, Git follow X-Style for arguments, etc.). You will not just learn facts, you will understand the rules behind them.

In practice, I limit myself to a few decks whose name should be very general: English for everything about the English language, Programming for everything related to my job of developer, even if that’s not code, General for everything else such as capitals, history, geography. But If you are enthusiast about history and create a lot of flashcards about it, you will probably need a deck only for history. In short, it depends.

Example

- English vocabulary

- English idioms

- English grammar

- English slangs

- Capitals

- Countries

- Seas

- English

- Geography

Advantage: Group flashcards according their topic and not their type. When you speak English, you need to know the grammar, some vocabulary, and maybe a few idioms. Everything is related and that should be reflected into your decks. Organize the information in the same way that you are using it (when programming, you are editing some code in your text editor using shortcuts, you are committing your changes using Git commands from a Linux terminal).

|

Tip

With Anki, I use tags to annotate the flashcards with the categories where they belong (vocabulary, grammar, idiom, country, capital, etc). This is very useful when you want to review, for example, only the English grammar. Anki lets you create filtered decks using these tags ( |

Random is better than linear

School often forces us to learn foreign vocabulary by topic. Most vocabulary books and online lessons are also organized like that. But should we learn all the vegetables before the means of transportation? Or the reverse? I would like to see you get off the plane at Paris airport, knowing how to say cucumber in French, but not knowing how to ask for help or a taxi. In the same way, I’m not sure knowing how to say a horse carriage in French will be useful to decipher the main ingredients on a French menu at a local restaurant.

An alternative that I have found more effective in practice is to learn the vocabulary according their frequency. There exist frequency dictionaries published as books or available online. This way, you will quickly know about car, bus, train, salad, carrot, and only after you have mastered the basic vocabulary, you will heard about hoverboard, turnip, etc.

This applies not just for vocabulary. You probably don’t want to learn all the vocabulary before learning the grammar, and only then the slangs and idioms. Or you don’t want to learn all Git commands before learning all Linux commands, and only then the shortcuts of your favorite text editor. Mixing up is more appropriate. Learn the basic Git commands, the basic Linux commands, the most useful shortcuts. Then, learn advanced Git commands, less widespread Linux options, etc.

In practice, I make sure to add flashcards at the appropriate time. I added the first thousand most common English words, and only after, the next thousand words, and so on. I added the most Git useful commands after reading an introductory book, and only after, I completed the list by reading a more authoritative book on the subject.

Advantage: As said before, our brain is not a perfectly organized warehouse but a giant mess of interconnected neurons. Injecting a little randomness into your decks reflects the complex nature of your brain. This rule is complementary to the previous rule Mixed is better than organized.

Stylized is better than unstyled

Flashcards doesn’t have to be just plain text. There are many ways to enrich them in order to make them more easier to learn. Here are a few tricks I use.

Tag to add context

When mixing various cards into the same deck (see rule Mixed is better than organized), a small hint can be useful to quickly grasp what we are talking about. For example, you can use tags in Anki to distinguish the subjects inside the same deck, but Anki doesn’t display them when reviewing. As a workaround, I prepend all my flashcards with the tag.

Example

Advantage: By systematically prepending/appending the tag/category, you don’t have to look for a clue in the question to get the context. You are directly focused on the question to answer.

Emphaze to highlight keywords

As explained by the rule Short is better than long, flashcards should be as short as possible. Another solution to shorten the time required to read the question is to highlight some keywords. The first time you review the flashcard, you will need to read the full content but with successive reviews, you will start recognizing the question, just by seeing the keywords.

Example

var, const, type, func) is important?

You can use different fonts when appropriate. I use a monospace font for every programming keywords or command names.

|

Advantage: Revisions are more effective since you lose less time reading the cards.

I also use highlighting on the back cards to make the expected answer explicit.

Example

Advantage: You only need to read highlighted text to check your answer. If you’re wrong, read the remaining of the text to get additional explanations (but keep the card short).

Colorize to create patterns

When learning a foreign language, you are constantly switching between two languages: How do you say car in French? What means voiture? To differentiate between these languages, I colorize each foreign word with the same color.

Example

I use the same logic on more elaborate cards, for example, when learning English expressions.

Marrying someone you’ve never met before is taking a leap in the dark.

C’est faire un saut dans l’inconnu que de se marier avec quelqu’un que l’on n’a jamais vu.

Marrying someone you’ve never met before is taking a leap in the dark.

C’est faire un saut dans l’inconnu que de se marier avec quelqu’un que l’on n’a jamais vu.

|

Tip

I use italics to differentiate examples from definitions. I follow this convention among all my flashcards. |

Advantage: Colors reduce the cost of context switching. When the flashcard appears, if it’s blue, you are looking for the translation in your native language, if it’s black (or any other color), you are looking for the translation in the foreign language.

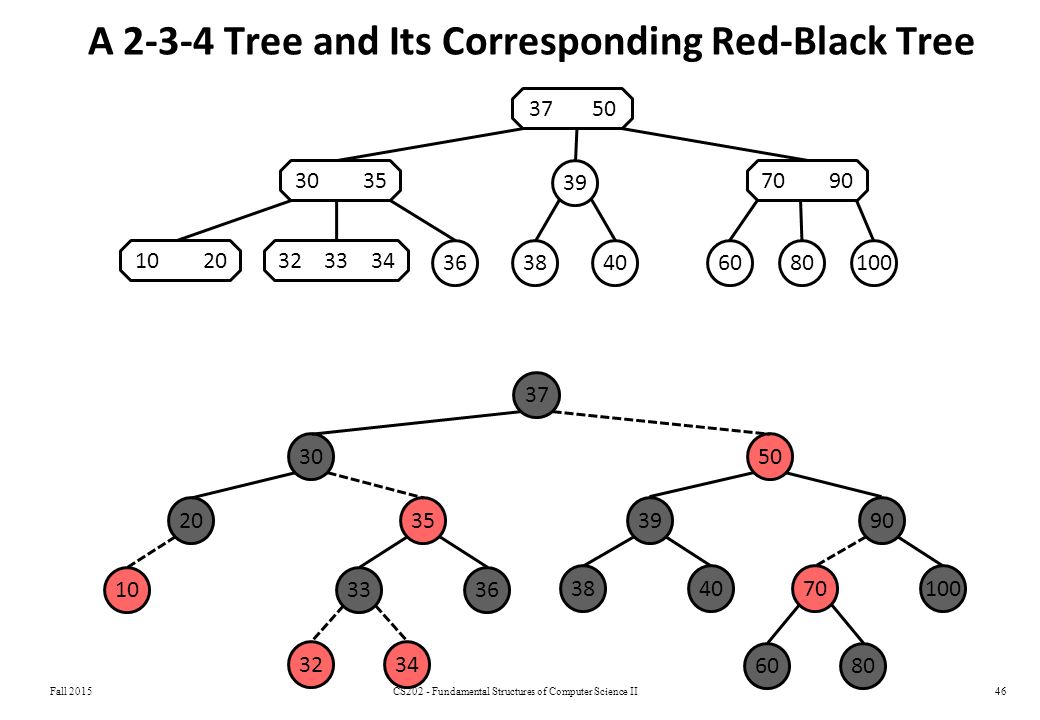

Illustrate to avoid wordy descriptions

A picture is worth a thousand words. Indeed, adding a (basic) schema can be a huge time saver. No need to read long paragraphs. Just have a look at the schema to understand the concept.

Example

|

Note for non-programmers

All computer programs produce data by manipulating data (inputs versus outputs). Internally, there exists many ways to store them, each one having advantages and drawbacks. 2-3 trees and red-black trees are examples of structures to store the same data using different formats. |

|

Tip

Anki also supports animated pictures (e.g., gif files). Very useful to animate some diagrams but keep the animation very short and the diagram not too complex. You don’t want to watch a video while reviewing your flashcards. |

Advantage: Learn the information using the best media. Sometimes, a small diagram or a sketchnote is all you need to get the idea. The simpler, the more effective.

Custom is better than shared

As said before, creating flashcards is not the most rewarding task. It sucks even when you knows the efficiency of flashcards. So, why not using shared flashcard collections. Anki offers shared decks, and there are numerous applications that was created the last years based on the spaced repetition system. For example, you can learn vocabulary with Memrise, and the grammar with Duolingo.

On the Internet, you will find numerous discussions about using those specialized (and often subscription-based) apps over using generalized applications like Anki. Personally, I tried these applications some years ago. I was using Memrise a lot at first, until I finally choose the centralized approach of using only one application, Anki. The reasons are numerous:

-

Learning is too crucial to depend on proprietary applications, which need viable business plans to subsist (a flashcard required several years to be really assimilated, I don’t want to reprocess the same cards tomorrow with another application). Using an OSS solution like Anki get you full control of your data. I wrote a blog post about how to export them in HTML just for the demo. Besides, with Anki, all your data resides on your disk. Ankiweb is used to synchronise them between your different devices (a small inconvenience compared to cloud based products that synchronize everything transparently).

-

As outlined in the rule Random is better than linear, you may want to learn the French vocabulary during the same review session as the French grammar. Using specialized apps, you have to switch between different applications. Making an habit is hard enough to not throw to many applications at it. Furthermore, there isn’t an existing application for everything you want to learn…

-

With Anki, I decide what I really want and need to learn. When using Memrise, you are limited to existing collections (e.g., 4000 words for an educated vocabulary, 500 most common words) What if you want to learn the 5000 most frequent words? You don’t control what you really learn, and this is, in my opinion, unacceptable (despite I found these apps very great with their clean interface and rich user experience).

Nevertheless, some subjects like vocabulary makes good candidates for sharing (look at Anki shared decks, the majority concerns foreign languages). Use them with caution to get started or if you have no plan to get really far in this particular language. Otherwise, adapt them to fit your own workflow (change the flashcard style, import them into the same deck, complete them with new cards, etc).

Advantage: Creating custom flashcards is the best way to stay in control of what you learn. The only downside is it requires time, a lot of time, but remember we lay the first stone of learning when we are creating them in the first place.

Afterword

As there isn’t a unique way of learning, there shouldn’t be a unique way to create flashcards. In this post, I have tried to expose what I learned from the numerous mistakes I made. There are surely more mistakes I will do. So, try what makes sense to you and experiment by yourself.

|

A good flashcard…

|

Resources

You may find the following articles relevant to contrast with what I said in this article:

-

https://www.supermemo.com/en/articles/20rules Published almost twenty years ago, this authoritative article stays as pertinent today as it was at the beginning of Supermemo, the first application using spaced repetitions, still in use today. A must-read!

-

https://fluent-forever.com/create-better-flashcards/ Written by Gabriel Wyner, the author of the book Fluent Forever, this blog post presents 8 useful tips illustrated with basic examples.