|

You are reading a translation of an old blog post published on my previous blog in French. |

Whilst native solutions to these problems will be arriving in ES Harmony, the good news is that writing modular JavaScript has never been easier and you can start doing it today.

The benefits of a modular design are obvious. Sadly, before the version ECMAScript 6, JavaScript provided no support to define modules. This was before AMD.

AMD (Asynchronous Module Definition) defines a format to define modules in JavaScript. Several script loaders already implement this standard. The most popular is RequireJS.

Using RequireJS, we will write scoped modules, without polluting the global namespace, with the additional benefit to declare explicitly module dependencies. From an implementation viewpoint, RequireJS is an extension of the pattern Module, widely implemented in JavaScript.

| RequireJS is published under the new BSD license and MIT. The code presented in this article has been simplified for obvious reasons and must not be used outside this learning context. This article is based on the latest version of RequireJS (2.1.16) at the moment of publication. |

Getting Started with Modules

AMD defines two main methods:

-

defineto define a new module. -

requireto define and load dependencies.

Let’s start by the method define:

define(

module_id /* optional */,

[dependencies] /* optional */,

definition function /* function instantiating the module/object */

);The first parameter is used to name the module. Often, modules will be anonymous (a best practice to ease their reorganization). Then comes the list of dependencies to load, that will be passed as the last parameter, the function responsible to really instantiate the module.

Here is an example:

define(

// => anonymous module

['foo', 'bar'],

function ( foo, bar ) {

// Return the value defining the module.

// This is the value that will be returned when another module

// depends on it.

return {

sayHello: function() {

console.log('Hello World’);

}

};

}

);require is most often used to define the entry point (the first file loaded by RequireJS) or inside the definition of a module as follows:

define(function() {

// Example inspired of http://addyosmani.com/writing-modular-js/

var isReady = false, foobar;

// require is inlined

require(['foo', 'bar'], function (foo, bar) {

isReady = true;

foobar = foo() + bar();

});

return {

isReady: isReady,

foobar: foobar

};

});| We will not go further in the presentation of RequireJS/AMD. Read the official API documentation for more details. |

A First Example

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>My Sample Project</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<script data-main="scripts/main" src="require.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>My Sample Project</h1>

</body>

</html>On loading, RequireJS inspects the special attribute data-main to find the first application module to load. This is the file main.js present under the directory scripts/:

require(["helper/util"], function(util) {

// This function is called when scripts/helper/util.js is loaded.

// If util.js calls define(), then this function is not fired until

// util's dependencies have loaded, and the util parameter will hold

// the module value for "helper/util".

var titles = document.getElementsByTagName('h1');

for (var i = 0; i < titles.length; i++) {

titles[i].textContent = util.toFunnyCase(titles[i].textContent);

}

});This file contains a simple call to the function require to request the loading of another module (helper/util) defining the function toFunnyCase. The remaining lines simply update the title of the HTML page using this mysterious toFunnyCase function.

So, let’s inspect this file scripts/helper/util.js:

define({

/**

* Capitalize one letter every two letters. (Ex: "Julien" => "JuLiEn")

*

* @param {string} str The string to format

*/

toFunnyCase: function(str) {

var result = '';

var uppercase = true;

for (var i = 0; i < str.length; i++) {

result += uppercase ? str[i].toUpperCase() : str[i].toLowerCase();

uppercase = !uppercase;

}

return result;

}

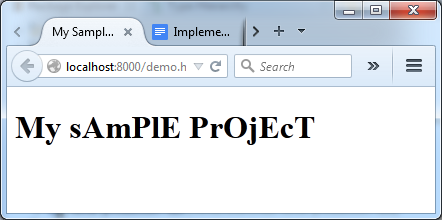

});The module is anonymous, without any dependencies, defining a unique function producing the following result when our page is loaded in our browser:

Our goal is now to remove the dependency on require.js, and to provide a custom implementation that we will write step by step.

RequireJS, Under the hood

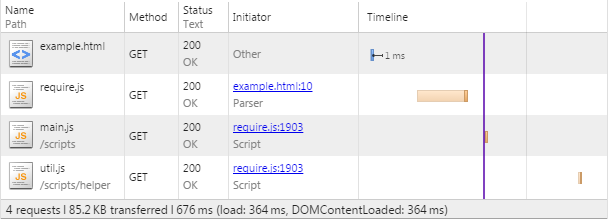

Before jumping headfirst into the code, let’s take a look at the HTTP requests sent by RequireJS on our example.

-

require.jsinspects the attributedata-mainto determine the first file to load, in our case,main.js. A first Ajax request is emitted. -

main.jscalls the functionrequire. One dependency is declared. The methodrequiretriggers a second Ajax request to downloadutil.js. -

util.jsdoes not have dependencies. The instantiation callback of this module is executed. RequireJS memorizes the result for the next step. -

We are back in the file

main.js. All dependencies have been loaded. The instantiation callback of this module is finally executed, receiving the previous module result in argument.

Let’s Go

We start by modifying the example file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>My Sample Project</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<script src="scripts/jquery-2.1.3.js"></script> (1)

<script data-main="scripts/main" src="scripts/require.lite.js"></script> (2)

</head>

<body>

<h1>My Sample Project</h1>

</html>| 1 | We import jQuery, not indispensable but convenient to reuse some utility functions. |

| 2 | We replace the library RequireJS with a new file require.lite.js that we will be the subject of this article. |

Here is the skeleton of the file require.lite.js:

var require, define;

(function () {

/**

* Main entry point.

*

* The first argument is an array of dependency string names to fetch.

* An optional function callback can be specified to execute

* when all of those dependencies are available.

*/

require = function (deps, factory) {

// TODO

};

/**

* The function that handles definitions of modules.

*/

define = function (id, deps, factory) {

// TODO

};

}());The code starts by inspecting the attribute data-main:

(function () {

var baseUrl;

// ...

$('script[data-main]').each(function () {

var dataMain = this.getAttribute('data-main');

var src = dataMain.split('/');

var mainScript = src.pop();

baseUrl = src.join('/') + '/';

require([mainScript]);

});

})();We split the attribute value to extract the dirname (baseUrl) from the basename (mainScript). This directory will be used as the base directory when loading other scripts. The code ends by calling the method require. Time has come to get to the heart of RequireJS.

Module

RequireJS relies heavily on the object Module whose constructor is defined like this:

var requireCounter = 0;

function Module(id) {

this.id = id;

this.depIds = []; // Module dependencies

this.depExports = []; // Dependencies values (1)

this.depCount = 0; // Counter representing the number of dependencies

// still pending (2)

// No id => it's a call to the function require => we generate a new id

if (!this.id) { (3)

this.id = '_@r' + (requireCounter += 1);

}

this.events = {}; // event => [listeners] (4)

this.url = baseUrl + this.id + '.js';

};| 1 | depExports will contain the arguments that will be passed to the instantiation callback of this module. After the loading of a dependency, we save the value in this array. |

| 2 | The instantiation callback must execute only when all its dependencies have been loaded. Using this counter, we know the number of dependencies that are still not completely loaded. |

| 3 | It is important to assign an id even for simple files containing a simple call to require. If this file is referenced several times, it will be loaded only once. |

| 4 | We implement the pattern Observer. Other modules can register to watch the progression. In practice, we are going to use it only to know when a module has been defined. (RequireJS generates a lot more events internally that are not useful for our basic example). What follows are two utility methods used to support this use case. |

Module.prototype = {

/*

* Register a new listener.

*/

on: function (name, callback) {

var callbacks = this.events[name];

if (!callbacks) {

callbacks = this.events[name] = [];

}

callbacks.push(callback);

},

/*

* Notify all listeners.

*/

emit: function (name, evt) {

(this.events[name] || []).forEach(function (callback) {

callback(evt);

});

}

};The object Module exists but nothing happens. It’s only when the method init is called that the magic happens, and precisely during the execution of the method enable.

Module.prototype = {

/*

* Init a new module.

*

* @param depIds Dependencies of the module

* @param factory Instantiation callback

* @param enabled Immediate activation enabled

* (used by require),

*/

init: function (depIds, factory, enabled) {

if (this.inited) {

return;

}

this.enabled = this.enabled || enabled;

this.factory = factory;

this.depIds = depIds || [];

// Flag indicating that the module is currently initializing

this.inited = true;

if (this.enabled) {

this.enable();

}

},

enable: function () {

this.enabled = true; (1)

// Enable every dependency successively

var module = this;

this.depIds.forEach(function (id, i) { (2)

var mod;

if (!registry[id]) {

mod = new Module(id);

registry[id] = mod;

module.depCount += 1; (3)

mod.on('defined', function (depExports) { (4)

module.depCount -= 1;

module.depExports[i] = depExports;

module.check();

});

}

mod = registry[id];

if (!mod.enabled) {

mod.enable();

}

});

this.check(); (5)

}

}| 1 | As for the method init, we memorize that the module has been activated. It prevents the module from being initialized twice. |

| 2 | We load dependencies transitively. We can enable the module before all its dependencies have been enabled first. We iterate over them, and if the dependency is new (this is the motivation behind the variable registry), we instantiate its Module, before trying its activation (recursive method). |

| 3 | The property depCount is incremented to indicate that we are waiting for the loading of this module. |

| 4 | We register to decrement this variable when the module has been defined. |

| 5 | There are two calls to the method check: at the end of our own activation, and for each dependency definition. Here is the code of this method check: |

Module.prototype = {

/*

* Checks if the module is ready to define itself, and if so,

* define it.

*/

check: function () {

if (!this.enabled) {

return;

}

if (!this.inited) {

this.load();

} else {

this.define();

}

},

define: function() {

var id = this.id,

depExports = this.depExports,

exports = this.exports,

factory = this.factory;

if (this.depCount < 1 && !this.defined) {

if (typeof factory === "function") {

factory.apply(exports, depExports);

} else {

// Just a literal value

exports = factory;

}

this.exports = exports;

this.defined = true;

this.emit('defined', this.exports);

}

}

};This method check tries to finalize the module (i.e., execute the callback). We start by checking if the module has already been initialized, in which case we just have to request its loading (= Ajax request). Otherwise, we try the method define.

define checks that all dependencies have been loaded correctly (using the property depCount). If every condition is satisfied, depExports is passed to the instantiation callback. Done! We publish a new event to propagate the news to other modules, which as we have mentioned before, listen attentively for this event, to try to call the method check themselves to finalize their own definition.

|

How to load a JavaScript file dynamically?

Several solutions exist, but the most widespread is to append a new tag |

We should now implement the two main methods defined by AMD. Using the object Module.

require

The definition of the method require is trivial:

require = function (deps, factory) {

var module = new Module();

module.init(deps, factory, true);

}We just have to create a new module that is initialized immediately. Its dependencies will be initialized transitively.

define

The method define is not obvious to implement, but neither too complicated.

Let’s take the example file main.js.

require(["helper/util"], function(util) {

// ...

});When this script is executed, we have seen that the method require triggers the loading of all dependencies (using the method enable). The script util.js is then executed:

define({

// ...

});We arrive in the method define, but we ignore the name of the module. So how can we finish its activation? What is the name to use to register the result?

The solution implemented by RequireJS is to memorize the arguments of every execution of the method define (in a queue, as several modules can be loaded simultaneously):

var defQueue = [];

define = function (id, deps, factory) {

// Allow for anonymous modules

if (typeof id !== 'string') { (1)

// Adjust args appropriately

factory = deps;

deps = id;

id = null;

}

// This module may not have dependencies

if (!Array.isArray(deps)) { (2)

factory = deps;

deps = null;

}

defQueue.push([id, deps, factory]); (3)

};| 1 | Not a string in first argument, we know this is an anonymous module, we shift the arguments in consequence. |

| 2 | Not an array, we know that the module has no dependency. We shift the arguments again. |

| 3 | Variables contains now the right value. |

We modify the method loading a script to declare a new callback. This function will be executed just after the method define, the perfect moment to reread previously saved information and to end the module instantiation.

/**

* Do the request to load a module for the browser case.

* Make this a separate function to allow other environments

* to override it.

*

* @param {String} id the name of the module.

* @param {Object} url the URL to the module.

*/

function load(id, url) {

var head = document.getElementsByTagName('head')[0];

var node = document.createElement('script');

node.type = 'text/javascript';

node.charset = 'utf-8';

node.async = true;

node.addEventListener('load', function() { (1)

completeLoad(id);

}, false);

node.src = url;

head.appendChild(node);

return node;

};

/**

* Complete a load event.

* @param {String} id the id of the module to potentially complete.

*/

function completeLoad(id) {

/*

* We iterate over all saved modules (define).

* If we find a module without id or with the given id,

* we proceed to the module initialization.

*/

var found, args, module;

while (!found && defQueue.length) { (2)

args = defQueue.shift();

if (args[0] === null) {

args[0] = id;

found = true;

} else if (args[0] === id) {

// Found matching define call for this script!

found = true;

}

if (found) {

module = registry[args[0]]; (3)

module.init(args[1], args[2]);

}

}

};| 1 | We trigger the callback on the event load. |

| 2 | We traverse saved values until finding our module. |

| 3 | We complete the module initialization. |

|

Congratulations!

Congratulations, our minimal rewrite of RequireJS is now complete. Less than 300 lines have been required to make our example works again. The complete source code is available here. |

|

To Remember

|

|

Try for yourself!

|