I love reading nonfiction books, particularly while commuting. I (try to) start a new book every week — a new language, a new framework, a new insight. There is so much to learn. But the truth is, after more than 300 books read in the last decade, I forgot (almost) everything.

I am not saying that reading is a waste of time. Not at all! My readings have profoundly influenced my way of thinking, how I approach my career, and I feel very indebted to the authors that dedicated a part of their life to the task. What I am asking instead is: what could I have done to remember more?

Memories are memorable

Most of what we see, what we hear, or what we read does not survive after 30 seconds. Those rare items whose survive start a perilous journey into our long-term memory facing a sad reality: our memories decay with time. The more distant the exposure to a subject, the less likely we remember it. But some memories disappear slower. What makes these memories stand apart is they are memorable — an interesting subject, a funny picture, a familiar face, an incredible piece of news, a beautiful landscape — the more memorable, the longer in the memory.

In theory, our memory acts as a giant network where each neuron may be connected to up to 10,000 neurons using synapses. In practice, it means if we want a given memory to stay for a long time, we better have to create connections with the most of existing memories. To do that, you need to arouse interest by choosing the best resources to learn. Every subject can be made passionate by choosing the right words, the right metaphors, the right examples. There is never a unique best resource. It depends on what you already know and what you want to learn. Do not read the reference book on a programming language if you are just writing your first program. Begin with a quickstart guide and when you are more comfortable about the syntax, read an advanced book to master the subtleties of the language.

The importance of creating connections explains also why seeing the Big Picture when learning something new is so important. Indeed, the Big Picture help us connect new knowledge with existing ones, and thus strengthen the comprehension and the retention of new information. In the highly praised book A Mind for Numbers, author Barbara Oakley compares learning with building a wall. Do you imagine a wall without mortar to glue the different bricks would pass the test of time? Of course, no. So, create connections and always make sure the mortar is dry before laying new bricks.

|

Key takeaway

Remembering requires to develop a personal relation with the subject. Don’t read a book because someone say you should. Be curious and follow your interests. What interest you the most at the present moment is what you will remember the best. And if something is so important, it will come back to haunt you anyway. |

Associations are keys

During our studies, we all have struggled with a subject that gave us a hard time. Some subjects like mathematics and foreign languages are challenging and it may not be obvious at first how to create connections.

All memory […] is based on association. Harry Lorayne, The Memory Book

Creating associations is something we do constantly. Digits are used to represent a quantity in the same way that letters are used to represent a sound. When a new information is difficult to grasp, it is often easier to try to picture something else than trying desperately to remember it the wrong way. Even Einstein fails miserably with rote learning. Author and biograph Walter Isaacson relates, "As a young student he never did well with rote learning. And later, as a theorist, his success came not from the brute strength of his mental processing power but from his imagination and creativity. He could construct complex equations, but more important, he knew that math is the language nature uses to describe her wonders. So he could visualize how equations were reflected in realities—how the electromagnetic field equations discovered by James Clerk Maxwell, for example, would manifest themselves to a boy riding alongside a light beam."

Author ShaoLan Hsueh, with her book Chineasy, gives us a formidable illustration of the key roles of associations. This mom of two British born children wanted to help them learn Chinese, one of the oldest written languages, and one of the most difficult to master, especially for Westerners. ShaoLan’s method is to transform Chinese characters into charming pictograms that are easy to remember. Here are some examples:

Visualizations are also used by all memory champions, who among their achievements succeed in remembering the order of a shuffled deck of cards in less than 30 seconds. As using pure rote learning is doomed to failure, champions use associations. When you see the ace of diamond, they see Michael Jordan slam dunking a basketball. The two of club is Charlie Chaplin swinging with his cane. The jack of space can be the Joker in Batman laughing insanely. And so on. Memorizing the deck of cards just comes down to imagine a story using these associations. It can be Charlie Chaplin (two of club) laughing insanely (jack of space) before receiving a basketball (as of diamond). This basic technique known as the PAO system (Person-Action-Object) is commonly used in major competitions and is very similar to the techniques used in the Ancient Greece by orators to remember their speech.

…[W]hen people say, "I forgot," they didn’t, usually-what really happened was that they didn’t remember in the first place. Harry Lorayne, The Memory Book

|

Key takeaway

Associations transform memories from insignificant to memorable. If something is hard to learn, it is probably because you should learn it differently. Be imaginative. It’s fun and it definitively works. |

Time always wins

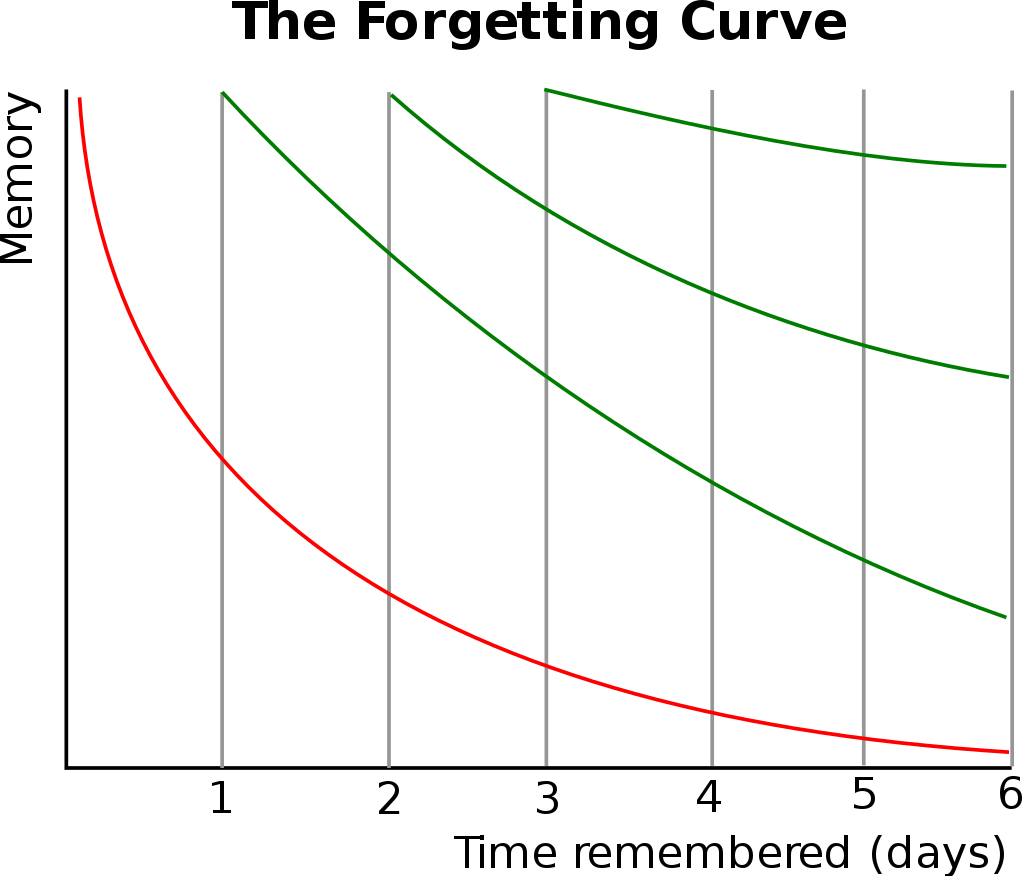

Memorable memories are not immune to decay, and with time, even the more memorable memory could become past memory. The solution is simple. We need to access the information before it disappears. By doing that, you are sending a clear message to your brain: "this is important to me." The following diagram illustrates the retention according the number of times an information is reviewed.

The numbers are only for illustrative purpose. What is important to notice is that memory decays more and more slowly over the revisions. By reviewing the same information at precise interval, we could fix a memory for a very long time using only as few as 5 to 7 reviews. This is exactly what Spaced Repetition is about. This learning technique is commonly applied to retain indefinitely a large number of items in memory. It is, therefore, recommended when learning a new language and you face the problem of vocabulary acquisition. While a paper and a pencil can suffice to apply spaced repetitions, there exist spaced repetition softwares (SRS) to help us store items and review them at the right time. The most popular application and the one I use is Anki.

Used by polyglots and memory champions all across the globe, Anki is the most versatile application but not the sexiest one. Compared to specialized applications — Memrise for vocabulary, Duolingo for grammar, Khan Academy for science — you have to create your flashcards from scratch with Anki (there exist shared decks but it’s anecdotal). What seems a disadvantage at first is its biggest strength. It’s take time but you have a total freedom, and as each person’s memories are different, this makes a real difference. You choose what to learn, and how to learn it, using associations that make the most sense for you. Everything is stored in the same place.

I have to confess, making Anki a habit is hard work. I started using it three years ago to learn design patterns, refactorings, and algorithms. It worked great during a few months, but then, I started missing the reviews. Very quickly, the number of cards to review was exploding. I almost abandoned but I was failing to remember again. To regain interest, I added a lot of flashcards to learn programming languages, bash commands, English vocabulary, and memory associations. The more you put into Anki, the more valuable your review sessions are.

|

Key takeaway

Accessing frequently an information in your memory is the best way to instruct your memory to keep if safe for a long time. Flashcards are your friends but like any habit, it’s hard work. Find a use case and give it a try. |

Conclusion

Remembering becomes easier when acknowledging how the memory works. Nobody is good at rote memorization. With good associations, an endless curiosity, and the discipline to test prior knowledge, remembering become accessible to everyone. This is only the first step. Once you know how to remember, the next step is to determine what to remember, a task far more difficult than it seems at first.

|

In practice

Here are some of the practices based on the principles presented in this post that I used. I urge you not to follow them blindly. I’m constantly experimenting.

|