|

This post is a follow-up of a previous post on simplicity where I discussed why not everything has to be simple. In this new post, I use the opposite argument to explain why everything doesn’t have to be complex. |

I think the next century will be the century of complexity.

Complexity is a scary word. Who wants to create complex systems? Who wants to interact with complex systems? But complexity is not as bad as it seems. The laws of Nature are complex and this doesn’t prevent us from living happily. We are complex and we can face it if we understand the rules of the game.

A System Primer

In my previous post, I detailed the main differences between a complicated problem and a complex problem. In short, if you can divide a system to inspect each part in isolation, you have a complicated problem. If interactions play a bigger role in understanding the system, you have a complex system where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Understanding the differences between complicated and complex systems is important because you will not use the same techniques to address them. This post will focus on complex systems. I will use organizations as an example to illustrate the main concepts.

A Complex System Is Not Just A More Complicated Problem

There are two main ways of seeing and approaching problems, one we have learned (and use a lot) and one we have ever known (but don’t use enough).

-

Reductionism gains understanding of the whole by dividing the system into simpler to understand parts.

-

Holism gains understanding of the whole by understanding the simpler parts in context and in relation to one another and to the whole.

For example, an organization is a group of persons, offices, computers, arranged into several divisions, departments, teams, where everyone is working towards a shared goal, assuming different roles. This view is an example of reductionism.

Reductionism excels at complicated problems—for example, understanding a program by understanding its main components is a good approach. But reductionism is a poor approach to complex systems. Two organizations can have a similar structure and be perceived as completely different. Google has teams organized in divisions spreaded into multiple offices like many companies. But what better defines Google is its culture and its vision, which determines how Google’s employees collaborate. Interactions define an organization. Interactions define complex systems.

Therefore, an holistic view is required when working with complex systems. In fact, we have always experienced holism. When walking in a forest, we don’t see trees as simply trunks, with branches and leaves. We know trees are part of a larger whole that is hard to define and that we call Nature. Reductionism is what prevents you from seeing the forest from the trees. Reductionism is what we used the most at work, because that’s what we learned at school. We need to integrate holism. The more ways of seeing, the better.

A Complex System Is Part of A Larger System

We live in a system of complex systems. Our cells, our immune system, our brain are examples of complex systems. Our organizations, our cities, our nations, our economy, and ultimately the entire universe are complex systems too. When you look up at a flock of birds, or when you look down at a swarm of ants, you are observing complex systems.

Each one of these complex systems is an open system. It means it doesn’t operate inside a well-defined boundary, but influences and is influenced by its environment. A company participates in a competitive market, a team is never totally autonomous, and your problems at home and at work affect each other, despite the common advice to keep a good work-life separation.

For the story, I wrote these lines the day an ant colony decided to explore my house to collect breadcrumbs on the dining table. There are better ways to start the day. This one reminded me that complex systems are everywhere, even where we don’t need them. It also reminded me that they are unpredictable. (I was not serene the next day when I got up…)

A Complex System Is Adaptive

To regain possession of our house (and finally eat my breakfast!), my wife and I had to react, and ants had to adapt. Ants started interacting with each other to find a way to escape. They changed their behavior in response to a change in their environment (like my wife and I do too).

Ants, like organizations are examples of complex adaptive systems (CAS). Actors in such a system adapt their behavior to the behavior of the other actors in an infinite loop. Driving a car relies on this same principle so that everyone can reach their destination. When facing an obstacle, you slow down, the car behind you slows down in turn, and so on, until having caused a traffic jam.[1] You may not be moving anymore, but at least, everyone is safe!

CAS systems exhibit other important properties we will describe in the following sections.

A Complex System Is An Infinite Loop

Complex systems use feedback as the main driver for adaptation, in the same way we use the results of our actions to determine our next actions.

We use feedback in learning, called corrective feedback, to avoid repeating the same mistake. We use feedback in career advancement, called performance appraisal, to evaluate our progression. We use feedback in feature testing, called user feedback, to measure the pertinence of new features. We even use feedback in machine learning, called reinforcement learning, to make better predictions. Feedback is important in any complex system and its study is an integral part of a field named cybernetics.

To give another example, organizations and Agile methodologies have a complicated relationship, to say the least. Some companies expect applying these methods will solve (some of) their problems. But the main goal of these methodologies is only to gather feedback (e.g., after a sprint or a milestone, during retrospectives or daily meetings). Agile will never be a recipe for success, just a way to introduce more feedback in the system so that organizations can learn and adapt. Or not.

A Complex System Is Unpredictable

Complex systems are nonlinear systems. There exists no proportionality and no simple causality.

The same action on the same system will invariably produce a different result, sooner or later. For example, new advertisement campaigns increase the company visibility, which attracts new customers, but too many ads and your customers will be bored and leave. Hiring new salespeople can boost your revenue, but after a certain point, your production system will become the limiting factor, which will delay shippings, makes customers angry, and diminishes your revenue. Therefore, what made you successful in the past will not make you successful tomorrow.

Similarly, the same action on two different systems is likely to produce a different result. Adopting the same methodology or copying the same practices than a famous company will not generate the same benefits. The vast number of Agile transformations that failed is the perfect example. Therefore, you must understand that what makes others successful will not necessarily make you successful.

A Complex System Is a Game

The branch of mathematics Game Theory modelizes the strategies among rational decision-makers, also called players.[2]

Working for an organization is like playing a game. Employees make decisions with positive or negative outcomes, ruled by the culture. Winning the game is realizing the company vision. This game is mostly:

-

cooperative (versus non-cooperative). Ex: You can form coalitions with other employees.

-

asymmetric (versus symmetric). Ex: Your ideas have probably not the same impact as your CEO’s ideas.

-

non-zero-sum (versus zero-sum). Ex: Your team can opt for a solution where nobody is totally satisfied.

-

simultaneous (versus sequential). Ex: You are “playing” at the same time than other employees.

-

imperfect information (versus perfect information). Ex: You ignore most of the moves made by other employees.

Therefore, if your organization is a game, there must be cheaters. When a team member spread a rumor, or express unwarranted attacks about a coworker, consider this a cheating move. Otherwise, employees will stop working together and start defending against attacks and keeping note of individual scores. This situation is common with companies with poor culture like a presenteeism culture or a dog-eat-dog culture.

What game theory also teaches us is that if we want to understand others’ decisions or reactions at work, we must put ourselves in other people’s shoes, and consider things from their point of view. But the theory assumes employees act rationally, which is far from being true in practice. Complex systems are more complex, but not chaotic!

A Complex System Is Not Chaos

If complexity is scary, chaos is even more dreadful. Organizations are getting more and more complex — more globalization, more innovation, more diversification, more transformations, and thus more uncertainty.[3]

Companies that were stable decades ago now operate in an unsteady state, and small perturbations can completely change the system behavior. When a system becomes extremely sensitive to those small perturbations, chaos is close. A butterfly flapping its wings in China can cause a hurricane in Texas (the Butterfly Effect), or how a small change can result in large differences later. That’s bad. But we have reasons to be optimistic.

More than othen, complex systems regulate themselves to produce spontaneous order, rather than the meaningless chaos often feared. Spontaneous order is also called emergence or self-organization.

You don’t need something more to get something more. That’s what emergence means.

winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics

The evolution of life on Earth or the Internet are examples of systems which evolved through this property, often summarized with the popular phrase "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts." Our intelligence and our consciousness are emergent properties of our billions of neurons. The Game of Life has attracted much interest because of the surprising ways in which emergent patterns evolve and are observable.

Organizations are also a great example of self-organization systems. They are created and controlled by humans, and at the same time, are controllable by no one (the hierarchy chart only depicts the chain of commands but definitely not how communications really happen). During the Covid crisis, numerous companies experienced remote working for the first time, which was unthinkable a few years ago, and yet, chaos didn’t happen. Employees changed their habits and most were even more productive. This illustrates perfectly the adaptive nature of organizations and their resilience.

Based on these examples, we observe that emergence produces non-trivial patterns without a blueprint. It’s just magical. Wind-produced sand ripples on the beach create order from apparent disorder. If you think about it, it’s mind-blowing.

Therefore, you must not be afraid of chaos (except if your company is subject to the volatility of the stock market, which is particularly chaotic during this crisis). In fact, you must learn to live at the edge of chaos, at the intersection between the predictability of rigidity and the randomness of chaos. This is where true creativity exists. This is where you want to be.

A Complex Problem

All companies know that too many people on the same team is not a good idea. Complex systems are defined by their interactions and the more people you add in a team, the more interactions are necessary for the team to align.

Therefore, most companies follow the two pizza rule introduced at Amazon: “if a team couldn’t be fed with two pizzas, it is too big,” which means six persons in a team is a good size. This way, interactions inside the team become manageable as the amount of information that any part of the system has to keep track of is reduced.

Most companies, however, overlook the interactions between the teams. If minimizing the interactions inside a team is important, applying the same logic between teams is even more important. From my experience, I have often heard, “We need to better communicate between teams” or “We need to exchange more.” As I will explain in this section, sometimes, the best communication is the one that doesn’t happen. Communicate better. Communicate less.

The problem is exacerbated by digital solutions. Messaging tools like Slack claim to bring teams together and make them more productive. Ticketing systems make it easy to fill the backlog of other teams. In practice, those collaborative applications have a dark side that slowly but surely kills your productivity.

Indeed, those solutions don’t change the nature of human interactions. A ticketing system allows you to create a request using a web form. A chat application allows you to ask questions using your keyboard. But in the end, human interactions don’t change. These tools don’t reduce the complexity, they hide part of it. Imagine the same actions done with only paper forms and face-to-face conversations. Your office would look like an anthill with employees wandering to deposit their forms to the right desk or wait in line to question a colleague. That’s not a good way to work. That’s not a productive way to work. But that’s what we do.

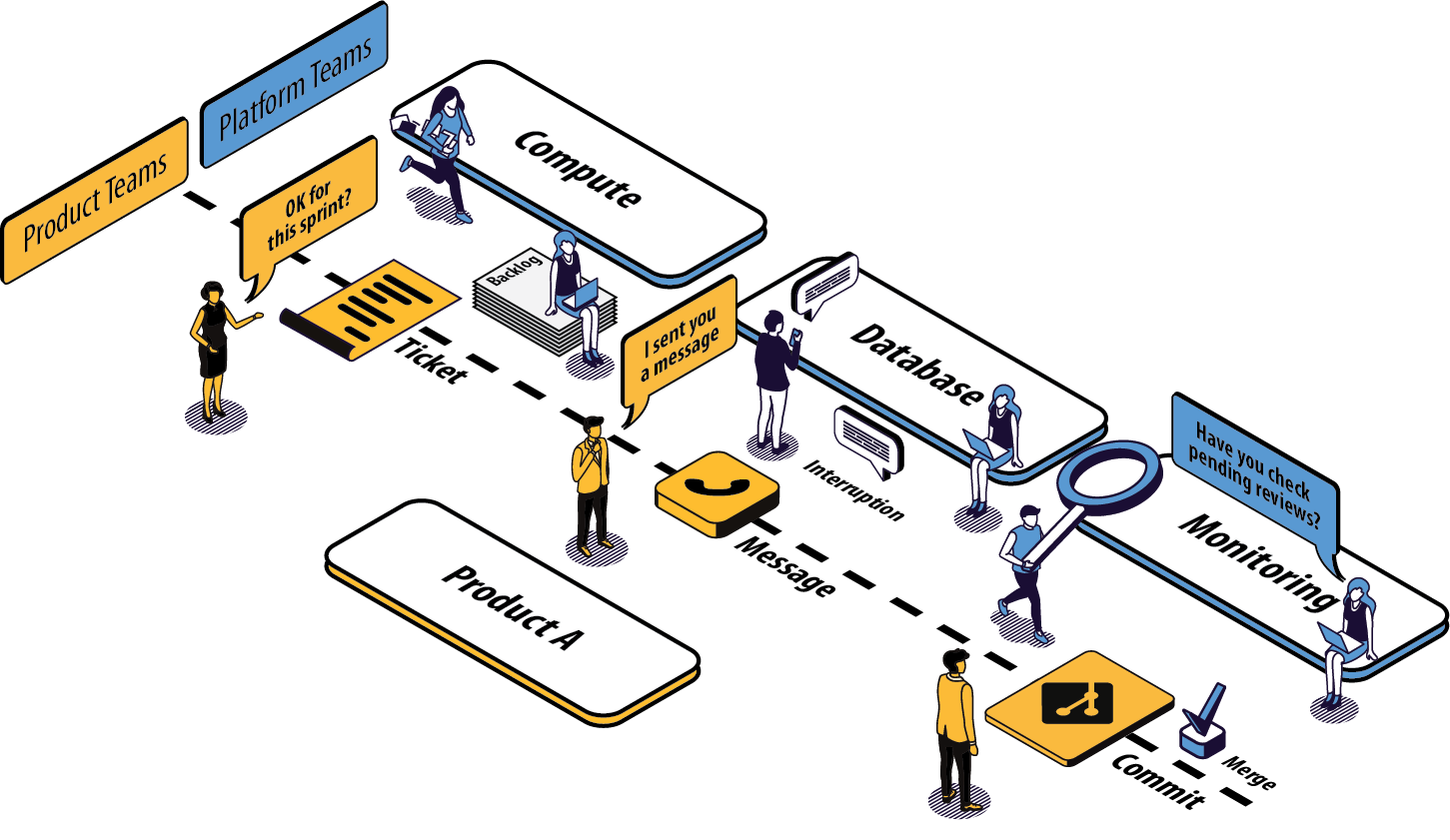

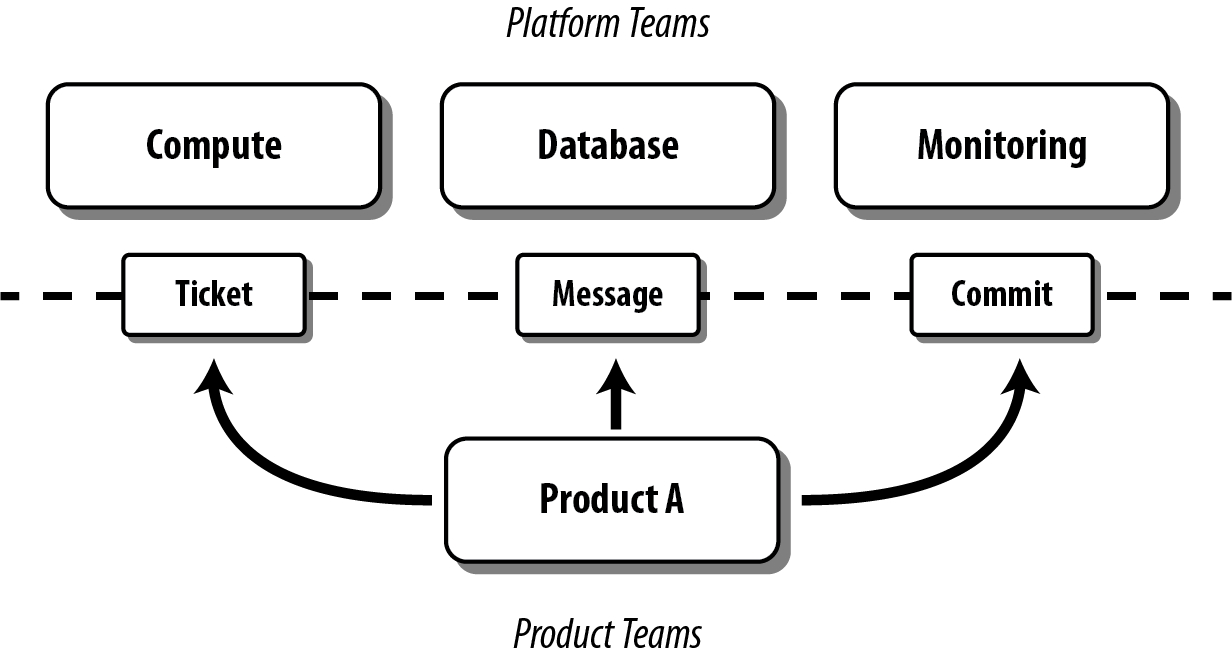

To illustrate my point, I will use the example of platform teams. As the number of engineers and products increase, the need to address common concerns globally becomes more and more apparent. Everyone doing what they think is best isn’t autonomy, it’s anarchy. If every team has to manage their own container orchestrator, load balancer, DNS server, monitoring solution, you will end up with an impressive list of technologies to maintain. Platform teams are a common solution to eliminate unnecessary diversity that provides no competitive advantage. Here is a diagram depicting a possible organization:

The diagram looks neat on paper (or on your screen). But only in appearance…

Architecture diagrams don’t describe the system. It’s a classic example of reductionism. They picture the structure, but not the interactions. They also ignore the time constraint (How long is the whole process for a product team to deploy?)

Here is the same diagram with human interactions explicitly illustrated:[4]

The situation is now very different. We observe the complex nature of the system in action. Humans are everywhere, and with them, many reasons for things to go wrong:

-

A ticket will not be processed immediately. The ticket is part of a backlog, and must linger and compete with others tasks before being resolved.

-

A Git commit imposes a code review, which means interruptions for the platform team, and an additional delay for the product team.

-

Messaging applications create a black market. Depending on who asks or to whom you ask, you request will be processed more or less quickly.

That’s not all! In addition, humans are not perfect (yes, I’m sure about that).

-

Confusion or misinterpretation will happen, leading to useless work needed to be redo.

-

Mistakes will happen, leading to incidents.

-

Conflicts will arise, leading to poor collaboration in the future.

A better approach is to turn as many problems as possible into software problems so that you can automate them. You will move faster and more predictably. You will increase the overall quality by the same token.

Concerning our example, a better strategy is for the platform to be available in a self-service mode. You may think, “That’s stupid. It will cost me so much. I will have to create APIs,“ and so on. First, based on the above identified drawbacks, are you sure the current situation is really less expensive if you include hidden costs? Second, we don’t need to start from scratch.

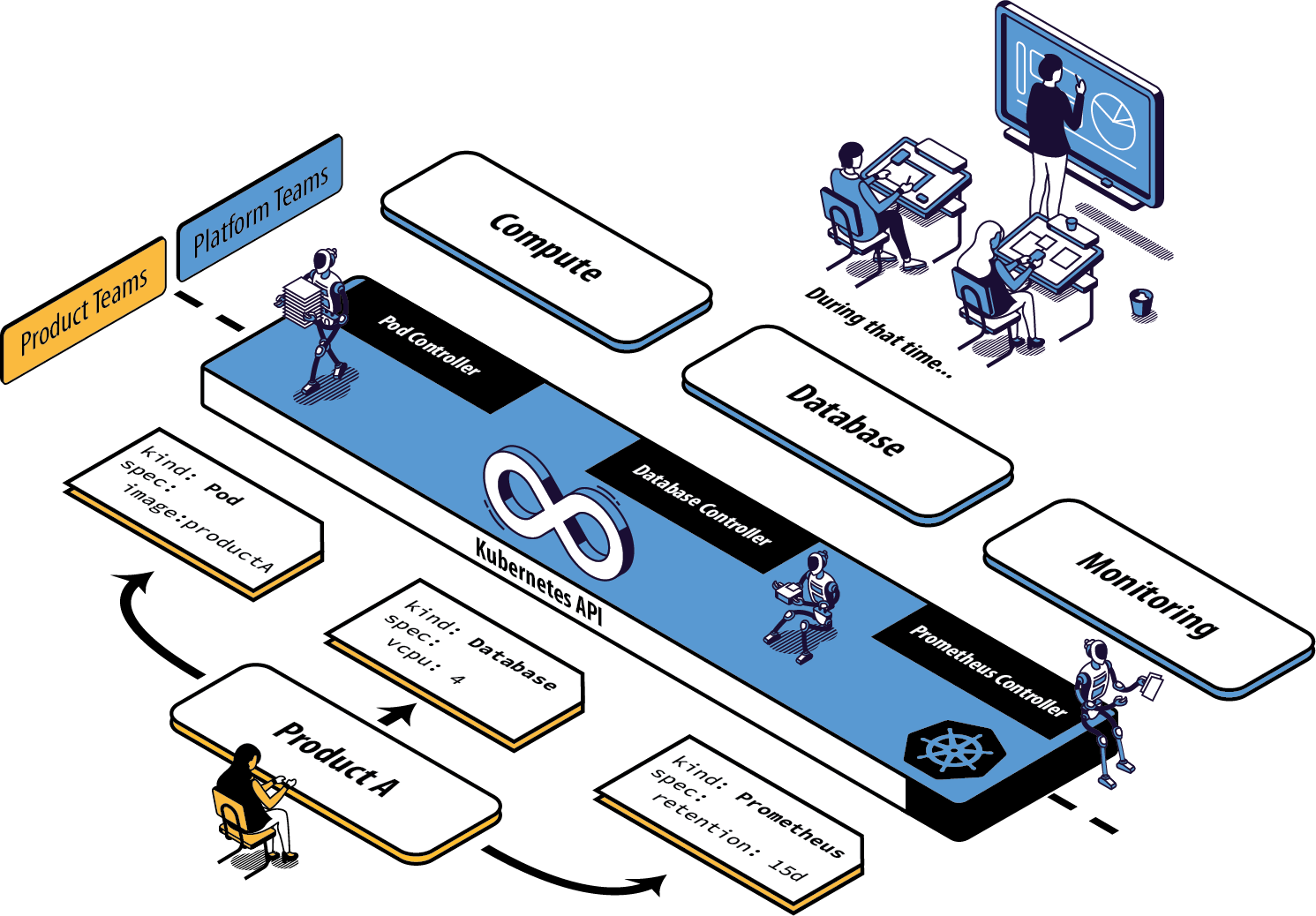

Let’s take for example Kubernetes. Kubernetes comes with an API for product teams to run their code packaged as containers. In addition, Kubernetes is extensible and makes it easy to create new controllers to manage new kinds of resources. (A Kubernetes controller is basically a container that watches changes in Kubernetes resources to start new containers on the behalf of the users.) For example, a product team can create a new resource of type Prometheus (i.e., a basic YAML file containing metadata), and the controller written by the platform team will be notified and will automatically start a new Prometheus container for the product team. This new workflow is illustrated in the updated diagram:

The end result may not seem much different from our initial solution. It’s the same components that are running. What has really changed are the interactions. We removed the interactions required for product teams to deploy their solutions. The solution is reproducible, easily testable, and more interesting for companies, we increased the velocity of product teams. Products can now be deployed in seconds, compared to days or weeks initially.

In the end, we replace human interactions by lines of code. We turn a complex system into a complicated problem. Of course, these lines are written by developers working as a team, and thus the complex system is still present. That’s true. Writing code in a team will always be a complex problem but running code in production doesn’t have to be complex. It’s mostly a complicated problem where the end goal is to execute deterministic instructions on a pool of static servers. Adding humans in the deployment process is accidental complexity.

|

Automation Fosters Collaboration.

Removing the human in the equation doesn’t mean reducing collaboration between teams. The challenge is to remove the interactions that don’t require true collaboration (a ticket to start a VM is nothing more than a command to execute). This way, employees can spend their time on truly collaborative tasks (analyze the system during retrospectives, find better solutions, identify technical debt, find new growth opportunities, elaborate new architecture proposals, etc.). |

This example has shown us that tools that claim productivity gains are probably not the tools that we really need. The best results require a shift of paradigm, a new way of working, not just a different way to do the same work slightly better. We will discuss additional strategies in the next section.

A few lessons

❌ Don’t put human everywhere

Companies need humans to do the tasks where humans really excel. We are better than computers in solving problems in which the rules are not obvious, in separating the wheat from the chaff in the flood of available information, and above all, we excel in just being human and understand other humans.[5] If a computer can do the same task as you do, it’s mean you are not using your full potential. It also means you unnecessarily complexify the system in which you operate.

By contrast, automation is a way to keep problems (at most) complicated, but not complex. As soon as a human is introduced in the workflow, the system stops being complicated—it becomes complex. There will be mistakes (you will delete the wrong server). There will be conflicts (you will misinterpret the intention of a coworker). There will be unexpected situations (you will feel sick when your company needs you the most). The classic response to these situations is usually to introduce new processes. The precautionary principle describes this tendency to add new rules to constraint a system even more. Some processes are useful (e.g., the procedure to adopt in case of a security breach). But if we can proceed without processes, nobody would complain.

| ✔️ Turn as many problems into software problems. Don’t create complex systems where complicated systems are possible. |

❌ Don’t control the system

Complex systems cannot be controlled. It’s like trying to control the flow of water. Instead, put on your bathsuit and go swimming. Interact with the system. It’s the only way to influence it.

We too often rely on models or methodologies to make sense of complex systems. But the truth is complex systems cannot be (fully) understood. Looking at its individual elements doesn’t reflect the interactions that define the system. It has to be studied as a whole, and as complex systems are often open, you need to understand their environment too. This means models are useful only if you accept they are incomplete, and don’t reflect the whole reality. No methodology will solve all of your problems. If you think there is only one option for your problem, you’ve probably not understood it.

So, if we cannot control the system, can we change it to produce more of what we want and less of that which is undesirable? The answer is yes, using leverage points—places in the system where a small change could lead to a large shift in behavior. It could be, from the less to the more impactful, changing a number (e.g., increasing the size of a team), a delay (e.g., using continuous delivery to accelerate the feedback loop), the flow of information (e.g., making information accessible where decisions are taken), a rule (e.g., ensuring all code are reviewed by peers), the goal (e.g., elaborating a new company vision), a paradigm (e.g., approaching problems with a software mindset).[6] As a note of caution, Jay Forrester, computer scientist from MIT, has observed that although people may find intuitively those leverage points, more often than not they push the change in the wrong direction…

|

Platform Teams (revisited)

To illustrate the previous leverage points, we can reuse the example where product teams were initially interacting with platform teams directly.

|

| ✔️ Address complexity with complexity. |

❌ Don’t let your left brain rules the world

Complex systems require an holistic view. Approaching complex problems with a purely analytic reasoning is the domain of reductionism. It is also the domain of the left side of our brain. This hemisphere excels at filling gaps in information to find coherence where there isn’t (a good definition for reductionism too).

We need to put our right hemisphere at work to fully appreciate the complexity of the situation.

It would be possible to describe everything scientifically, but it would make no sense; it would be without meaning, as if you described a Beethoven symphony as a variation of wave pressure.

The most successful, and creative persons including Albert Einstein, present a well-balanced brain, where both hemispheres are used symmetrically.[7] Techniques exist to solicit the right side of our brain. Taking a shower or walking alone are good triggers. Meditation is also known to reinforce the connections between both hemispheres.[8] In all cases, you must start paying attention when your left hemisphere is taking control of your mind.

| ✔️ Listen to your right brain. |

❌ Don’t fool yourself

Continuing on the previous point, we are not equals when it comes to complexity. The Myers–Briggs Type Indicator is a widespread test to determine what is your personality type.[9] Each type is identified by a four letter code that you have probably seen on some LinkedIn profiles. For example, INTP, aka the “thinker”, represents the position on four different scales (Extraversion (E) vs Introversion (I), Sensing (S) vs Intuition (N), Thinking (T) vs Feeling (F), Judging (J) vs Perceiving (P)). In particular, I would like to zoom on this last scale.

-

Judging individuals are decisive, thorough and highly organized. They value clarity, predictability and closure, preferring structure and planning to spontaneity.

-

Perceiving individuals are very good at improvising and spotting opportunities. They tend to be flexible, relaxed nonconformists who prefer keeping their options open.

These traits answer questions like, “Do you prefer spontaneity or certainty?” “Do you feel more comfortable acting with all your ducks lined neatly in a row?” Or “does a certain amount of flexibility or chaos excite you and prove motivating?”[10] Clearly, you will not demonstrate the same enthusiasm about complexity based on your score on this scale. The judging trait values structure, and translate into rigidity in practice. The perceiving trait is better equipped with figuring things out as they go, and translate into flexibility in face of complexity.

Even if you cannot change your inborn personality type, you can (and should!) influence the aspects of your personality that you are unhappy with.[11] By developing a better comprehension of complex systems, judging individuals will be able to find the minimal structure they need to really appreciate the reality of complex systems.

| ✔️ Understand yourself and you will better understand the world around you. |

Conclusion

We have finished our introduction of complex systems. We have reviewed the main concepts, and appreciated their manifestation in the world around us. We are part of a system of complex systems. The current economy is made up of organisations, which are made up of human beings, which are made up of cells—all of which are complex systems.

The common approach to dealing with complexity is to reduce or constrain it. Organizations are divided into departments. Software applications are designed around modular components (e.g., microservices). However, while it may make each part simpler to address, interactions must not be ignored as outlined by our example with platform teams. The most challenging problems encompass several teams or happens in the network between software components. The goal is thus to find the right balance between simplifying a problem to make it manageable while retaining enough complexity to make it relevant. This is far easier said than done, of course.

Learning to appreciate complex systems for what they are has profoundly influenced my way of thinking, at work, and in general. Complex adaptive systems are surprising. Their capacity to respond to change, to adapt, to learn is fascinating. Being part of an organization and observing these dynamics at work is so much fun, despite observing too often managers who try to “control” the system, which is never a great idea. Managers need to be part of the system, interact more with their collaborators, and be more present. Self-organisation systems will not necessarily lead to chaos. Order emerges from disorder. That’s the magic of complex systems. That’s how complex systems work.

There is much, much more to complex systems than presented here. The biggest challenges of our century—war, hunger, poverty, and global warming—are complex system failures. We will not solve them by fixing one part in isolation. We may not solve them at all, especially if we don’t better understand how complex systems work.

|

Key Takeaways

|